Twiggs Lyndon & Steve Morse Discuss Duane Allmans Hotlanta Les Paul

MLA • April 29, 2020

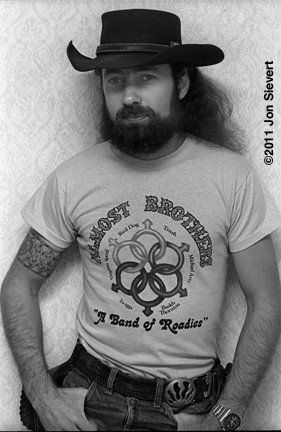

Twiggs Lyndon Talks Gear: An Unpublished 1978 Interview

Best known as the Allman Brothers’ road manager, Twiggs Lyndon also worked for Little Richard, Percy Sledge, and the Dixie Dregs. A wizard with mechanics, he described himself as “a hydraulic, mechanical, electrical person” who specialized in fixing problems. Musicians who employed him remember him as tough, resourceful, and loyal to the core. He was especially close to Duane Allman. The band thought so much of him that they included his inset photo on the back cover of the Live at Fillmore East album when he was unable to attend the photo session. (At the time, Twiggs was in a Buffalo jail, awaiting trial for first-degree murder following a scuffle with a club manager; he was eventually acquitted.) Twiggs continued to work with the band through the mid 1970s, when Chuck Leavell was a member.

In 1976 Steve Morse, a music student at the University of Miami, and some friends recorded a self-financed album called The Great Spectacular. Naming themselves the Dixie Dregs, Morse and bandmates moved to Augusta, Georgia. “We began blitzing the record companies with demos,” Morse told me in 1978. “People said, ‘Wow, that’s a weird band,’ but nobody was willing to do anything with it because it was instrumental music.” Then, Morse continues, “around Christmas 1976, we got on a gig with Sea Level in Nashville, and freaked out Chuck Leavell and Twiggs Lyndon. So when we finished playing, I talked to Twiggs about working for us. I was feeling sort of depressed because I knew we couldn’t afford him, but he said, in short, that he’d work for nothing, or whatever we could give him. The next day Chuck and Twiggs called up Phil Walden at Capricorn Records and gave him a big pep talk about the band. Phil agreed to do a personal audition, so we played on the floor of a disco club in Macon, Georgia. He said, ‘Okay, we’ll do it.’ We got the contracts together and signed.” In addition to serving as Dixie Dregs’ road manager, Lyndon became a mentor to the young musicians. His photo appeared on the back cover of the Dixie Dregs’ debut album, Freefall.

I met up with the Dixie Dregs for the first time in California on June 8, 1978. During my interviews with Steve Morse and bassist Andy West, both musicians encouraged me to talk to Twiggs. Steve introduced us. I liked Twiggs instantly. In those days, Levi jean jackets only had pockets on the outside, and Twiggs showed me how he’d modified his by taking the back pocket off of a pair of Levi pants and sewing it on the inside of his jacket. When I mentioned that that’d be a useful pocket for hiding the band’s cash, Twiggs grinned, “It’s even better for a pistol.” Twiggs invited me back to his custom tour truck to talk shop. Looking at his watch, he told me, “I’ve got 25 minutes before they clear the stage.”

****

Steve Morse tells me that you put his effects board together.

Yeah. It wasn’t a master task or anything. He had a board that was sort of mocked together. Everything was falling off of it, and he wanted to add some things to it. So we had a few days off, and he drew me a diagram of where he wanted all the pedals and everything. He had to go to another city, so I stayed in Alabama and put the thing together for him. Truthfully, at the time that I built it, I did not know what it was that I was building. In other words, I just placed them where he wanted them, and he said, “A wire comes out of this hole and goes over there.” It was the most complex thing that I had ever seen.

Steve designed it.

Yeah, he designed it. He plays through two amps. He plays through an Ampeg V4, which is used for what he calls his main signal. That’s his straight guitar sound. He then uses an Acoustic head – I’m not sure of the model – for his echo sound. He has an Echoplex, and he has an Echoplex footswitch on his board, plus a volume pedal to control the volume of the echo. So he can have the volume off, cut the Echoplex on, and then be playing a line and fade in the volume of the echo sound with the volume of the main signal and still be as loud as he was playing originally. If he could use two feet at once – and he damn near can – he could cross-fade it. In other words, he could fade the main signal out because he’s got a volume pedal for the main signal. I believe that he has a volume pedal for the synthesizer. He uses Bob Easton’s 360 Slave Driver and a special pickup in addition to four pickups that he’s already put on his guitar. So that pickup drives the Slave Driver. I think the Slave Driver is a pitch-to-voltage convertor, so to speak, and it drives the Minimoog which he has up there. He was an on/off switch for that and a volume pedal for that. See, I take care of the keyboard rig and the bass rig.

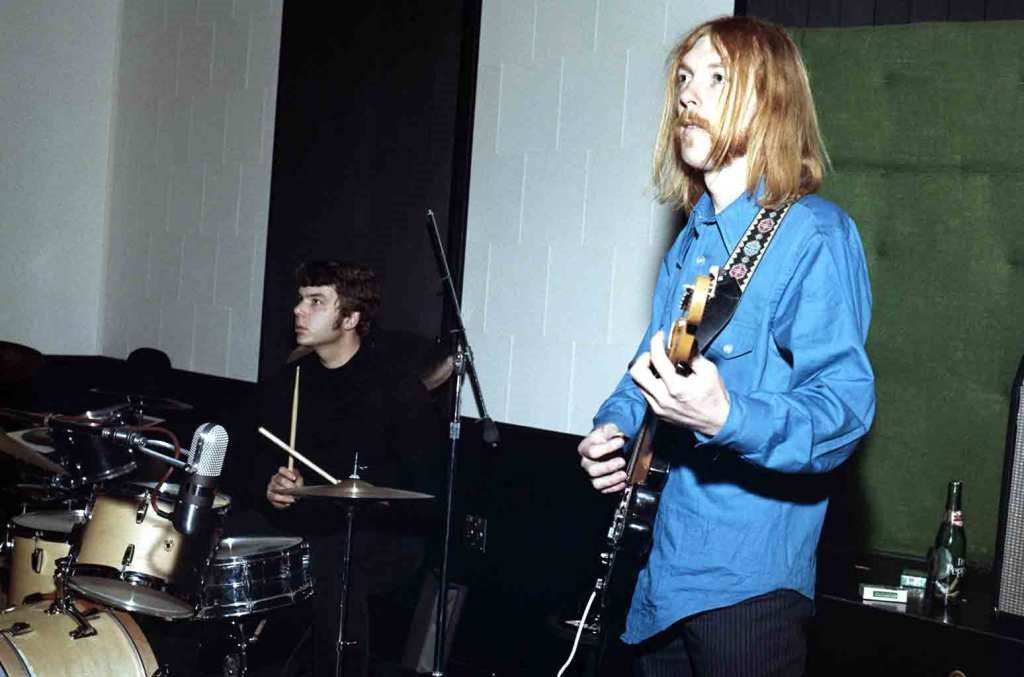

Dixie Dregs, 1978: Andy West, Rod Morgenstein, and Steve Morse. Back row: Mark Parrish, Allen Sloan.

Tell me about the Andy West’s bass rig.

The bass player and the guitar player really have their head together with electronics. They know how to achieve the sound that they want. The bass player even built his entire rig, and he put it together. He said, “Twiggs, what I want to do is have a pedalboard that has all this on it, and I want to have an effects rack that has all of these effects in it.” We hired a new keyboard player at the same time that Andy was trying to build the bass rig. The keyboard player had played around in Atlanta, and none of his stuff was ready to go on the road. This is Mark [Parrish]. He had no cases, no good wires. So we had like six, eight, ten days off, and I went to work during the off period. The band was rehearsing, to teach Mark the songs, and I went to work building the keyboard rig, and Andy went to work during the off-period doing his new bass rig.

Did he use the same kind of a rig you invented for the Allman Brothers?

Uh, I hadn’t used any of those devices for the keyboard. [Pauses.] Necessity is really the mother of my inventions. If you can tell me that you want that glass [points to a glass on the table] to sit here and be able to tilt left, right, and go up but not go down, and only go sideways when it’s going down – you know what I mean? – I can make it do that. But unless there’s a need for the glass to do that, I’m not going to sit around and design a mechanism to make that glass do that. So I said to Mark, “Well, what do you want?” He said, “I want to play the organ, but I wants these pedals, the wah wah pedal and all these things hooked up. I want the organ higher than it is now.” I said, “How much higher?” So he showed me. “And I want the keyboard here, but I want it higher.” And then I just sort of figured out the best way that I could figure to make all of it sit in a relationship. He plays a stock [Hammond] B-3 and a stock [Fender] Rhodes. He has a volume pedal under the Rhodes. I won’t work for a band with a Rhodes that does not have a board underneath it with a sustain for a stage monitor. You know the sustain pedal scoots all over the place? With Chuck [Leavell] that’s one thing I did use. For Chuck, I had a piece of plywood.

It’s real simple. Anybody can do it. You just take a piece of three-quarter-inch plywood, take some of those wood-boring bits, and bore three-eighths of an inch down into it where the legs will sit. So the legs to the piano sit down in those notches. The board is slightly larger than the perimeter of the four legs. And then you go and use a plumb bob. Hold it up there where the hole is and find the exact place where the sustain rod wants to come straight down. And then mark that and then mount the sustain pedal. You have to put little spacers, but it’s already got screws, those little rubber feet. Ditch those, and just come through the bottom of the board with four quarter-inch coarse-threaded screws. Counter-sink ’em, and you bolt the sustain pedal to the board. So if anybody hits the entire affair, then the entire affair moves together, as opposed to the pedal scooting here and there. Chuck didn’t use all those gadgets and pedals and things.

But if they want to use pedals, then there’s the board to bolt them to. With Mark, he wanted to stand up and play the piano, so he also wanted it raised up. So I built him that little box, and the piano sits up on the box. The sustain pedal is bolted down inside the box, and the rod comes through the edge of it. So it elevates it, and it houses the volume pedal and the sustain pedal for the Rhodes. I use it to store the legs in, so I don’t have to put the legs in the lid to the Rhodes. It works real good, but then it’s not necessarily the right thing for anybody but Mark. There’s some ideas that’s probably in it that everybody could use, but if you want to sit down and play the B-3 at a normal height, then the box that the B3 sits on – we cut the legs off the B3 because all the space underneath the B3 when you put it in a Carlo case is wasted, right? There’s nothing under there, unless you use those bass pedals.

Anyway, the bass player can tell you best about his rig. He has a synthesizer. He has one of those 360 Slave Driver things, but he doesn’t have a keyboard. He has an Oberheim, so he didn’t have to buy the keyboard. Morse already had the Minimoog, so he just used it instead of buying an Oberheim. And if push comes to shove, we could use his Minimoog for Mark to play, if Mark’s Minimoog went out. It gives us a spare Minimoog. I guess Steve would let us borrow it [laughs].

Do you enjoy working with the Dixie Dregs?

Twiggs depicted on the Dixie Dregs’ Freefall abum.

Yeah. The guys are really great. They are much more advanced. I’m a hydraulic, mechanical, electrical person. I understand all of those things. I know a little bit about electronics, but not a great deal. See, I’m a road manager. I was a road manager when I started in this business. We fired a couple of roadies in the Allman Brothers, and by that time we had like three or four road managers, so we were short roadies. I was an electrician in the Navy, and I play a little bit of guitar, so I knew how to plug an amp in, you know. So I volunteered to be turned into a roadie. There’s a lot less mental pressure being a roadie as opposed to being a road manager, especially working with stars. You know, they’re a little rougher to handle. So I enjoyed being a roadie, but I cannot repair an amp. Steve Morse and Andy West probably have the heaviest electronics knowledge in the band. I figured out how mechanically would be best to make Andy’s rig road-worthy. I don’t know if you see how it packs up, but we call it the “Black Monster” – that box with all the devices in it.

He has a pedalboard, but the pedalboard is built into the lid of the Carlo case, you see. So when the gig’s over, we take his pedalboard, unplug that multi-pin connector from it and from the box, roll it up and store it. Then we just take the pedalboard and turn it over, and it fits upside-down on the top of the box. Then there’s a protective front that goes on. We had to have the front so that he could have access to the things, and also have the lid that we turned into the pedalboard have one side that would be vacant. In other words, you have to step over that lip to mash the pedals. But as it is, that wall was not there. So it’s real easy to pack. The entire bass rig has four cables – it has one power cable, one signal cable that sends the signal from the direct box to his amp rack. Then it has two speaker wires – one to his cabinet for his lows because he’s crossing over, and one for his cabinets for his highs. That’s four cables. Oh, there’s a fifth cable, which is the multi-pin cable, and there’s a sixth cable, which plugs in his guitar. So I guess there are six cables. But it’s the most concise and fastest rig to set up and tear down.

How much time does it take you to set up?

It really depends on whether we have stagehands or not. We played with Billy Cobham at the Roxy, and there was not a lot of room. Billy Cobham’s crew were princes – they were so helpful! They were the stars, man, we were the flunkies – you know what I mean? And it was their stage, and they moved anything that had to be moved in order to permit us to be able to play. Both of us made concessions, but they went out of their way. Anyway, we cleared the stage from the time that the Dregs stopped until the time we had all of our stuff out of the way – hidden or off the stage, whatever we had to do with it – it took about eight minutes. And when we play as an opening act for Charlie Daniels, we can clear it with stagehands in between seven and nine minutes. It’s made to come offstage in a modular fashion. We use banana plugs in the back of the amps, which have two great advantages. One, they unplug readily. And two, you can see both connections. With a dual banana plug, both wires are soldered right there on the outside. So when I take the wire and go to plug it in every night, I just look. If either one of those connections is broken, you can see it, whereas if you use a phone jack, you’ve got to unscrew the cover off. If somebody steps on one or one breaks loose, you can find the problem by simply having a flashlight and walking back there and do an outside inspection without unplugging each cabinet, unscrewing the thing off, and looking at it.

How many people do you take on the road?

We travel with a complement of eight right now. One road manager – me – and then we have three roadies, counting me, and we have two truck drivers, counting me and one of the two roadies, and then we have a sound and a light man, which is the other two roadies. That’s three people – all of that [laughs]. And then we have five musicians, and they sure do their share of playing! They’re great. We all travel on one 18-foot van-body truck with all of the equipment. Somebody should do an article on the truck, because there lot of things happening there that bands could use.

Jas Obrecht interviewing Steve Morse in Twiggs’ truck, June 8, 1978.

Like what?

It’s not the most ingenious, but the greatest one is a spare battery under the hood. When they put automobile engines in trucks – a large V8, like a GMC truck has a large Chevvy engine in it –there’s more room under the hood than you would find under the hood of the Chevrolet with the same engine. So there’s room for a spare battery box. So we bought an extra Die-Hard, put it in a box, grounded the battery right there at the block with a short ground strap. Then I got a 25-foot roll of battery cable, zero-gauge or something, as big as your finger, and manufactured a long cable. I ran the battery positive back underneath the truck and ran it up through the floor with a water-tight string relief. In the cab we have bucket seats, and I had a 60-amp household square-D breaker box – no fuses, just a breaker switch – I had that welded to the rear of the cab wall, and I ran the cable inside the box, put it to the switch. It came off the other side of the switch, through another water-tight string relief, out of the cab through the floor. I ran underneath and put one of those tabs under it that allowed me to put it on the starter solenoid where the other battery positive terminated from the original battery. Okay? That switch is off right now. But while using the lift gate, etcetera, etcetera, or leaving the lights on overnight – whatever happens – when you come out and turn the key and the truck does not start, you do not get out of the truck, you do not push the truck, you do not ask for jumper cables. All you do it reach back, flip the switch, and you have a brand-new 12-volt battery that’s not been used, and you just crank it right up. And then as you drive a few minutes, you flip it off and the alternator recharges.

I’ve got about $2,000 worth of Snap-On tools that go in a Carlo airline case, and they’re packed the last thing in the truck, so we can get them out easily. And I have a spare brand-new alternator in a watertight compartment outside the truck – it’s a big box with big locks on it. It’s got a spare alternator in there, a spare water pump, spare fuel pump, spare starter motor. It’s got a complete spare ignition system, like wires, spark plugs, points, condenser, rotor, distributor cap. I’ve got spare air filters. I’ve got a complete set of spare fan belts, spare universal joints. Just about anything that can disable the vehicle, we can stop, fix it, and go on. When it gets to running ragged, we just stop and tune it up, and then go on. I carry a strobe light to time it. We have an altimeter in the truck that we bought at an airplane service store – see, cars and trucks that are sold in Denver, for example, are timed differently. There’s like a 12-degrees advance on Chevrolet engines because there’s no air [oxygen] up there. It would be nice if they made automobile carburetors with adjustable main jets, but they don’t. So on the way home, when we get to 4,000 feet, I stop the truck and get out and reset the timing to 12 degrees. And then when we get back down to 4,000, crossing the Rockies, I reset it to 8. I carry a meter to set the points with. The truck’s got . . .

[At this moment, one of the roadies stuck his head in the door. Twiggs asked, “Is that it?” The roadie responded, “Yeah.” Twiggs, ever the pro, instantly said, “Got to go then,” shook my hand, and departed. I never saw him again. Seventeen months later, Twiggs Lyndon, 37, perished in a skydiving accident near the town of Duanesburg, New York.]

Epilog: Twiggs Lyndon and Duane Allman’s Sunburst Les Paul

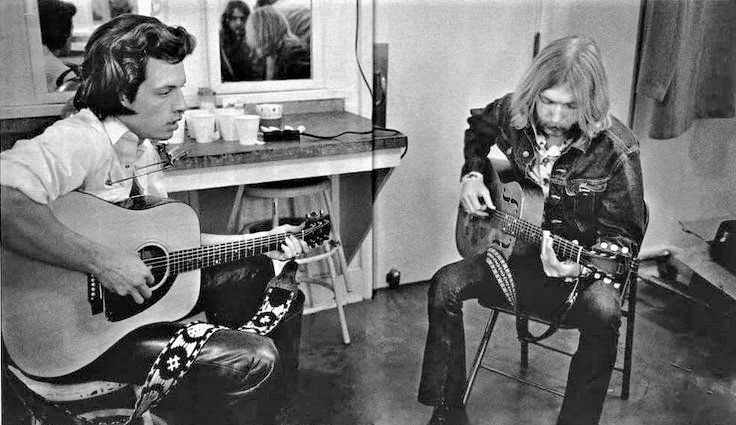

At the time of his death, Twiggs Lyndon had Duane Allman’s famous tobacco-sunburst Les Paul on the road with him. A few months after the skydiving accident, I asked Steve Morse what had happened to the guitar. “We were up in New York at the time,” Morse explained, “and I just took responsibility of carrying it around until I was able to give it to Twiggs’ brother Skoots in Georgia. Now it’s at Twiggs’ parents’ house in Macon. I use that guitar when we record, and they’ll let me use it pretty much when I want to, but it’s with his family.”

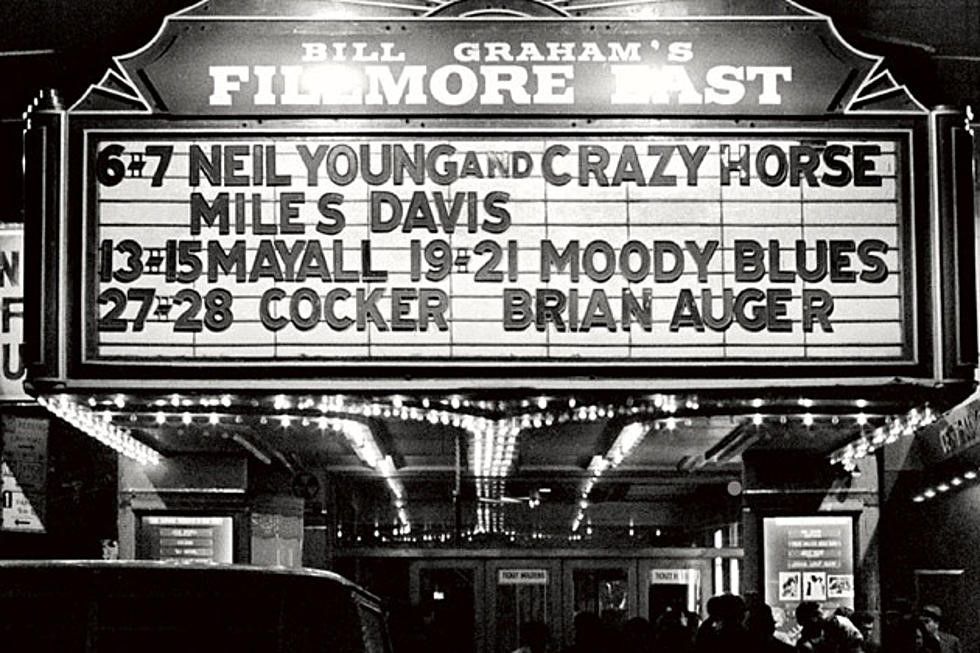

Steve Morse described the guitar as “a Les Paul Custom with tiger stripes and a sunburst paint job. It doesn’t have a pickguard, and the neck looks like a regular Les Paul neck, a sort of dark brown. It was cracked once, but Twiggs had it fixed when we were in California. And it’s got regular humbucking-looking pickups, but the one in the lead position is so intense! It’s so powerful. Something is so right about it. That’s the main thing about the guitar. I think the reason Duane had that guitar is because it would scream so much on the lead pickup. I remember Twiggs saying that Duane used that guitar on Layla and a lot of the Fillmore East. He like to use it for songs where he’d switch from playing regular fingerstyle to slide. I’ve used the guitar for solos on every [Dixie Dregs] album, just about. You can hear it on the melody of ‘Cruise Control,’ the slide guitar parts in ‘Rock and Roll Park,’ and in ‘Twiggs Approved’ there are two short guitar solos – one is in a regular style and the other is slide, and both of those are on the Les Paul.

“That guitar of Twiggs’ has gone through a long journey,” Morse continued. “Twiggs traded a car to Gregg Allman to obtain the guitar. Twiggs had a lot of old-time cars, in really good shape, and it was one of those. It wasn’t like Gregg was just giving the guitar away. He knew that Twiggs would really take care of it. At a time when Twiggs was really broke, someone offered him $15,000 for the guitar, and he wouldn’t take it. Twiggs all along was planning on giving it to Duane’s little daughter when she turned 18, so the family is holding the guitar until then. The reason Twiggs was gonna wait until then is he didn’t think that the girl would realize what she had. And Twiggs was just that kind of person – the principle of the whole thing was more important than anything.” [In the comments at the end of this article, Twiggs' brother Skoots explains how this guitar was, in fact, presented to Duane's daughter, Galadrielle Allman. Another brother, John, provides more insight into its history.]

Thanks to Steve Morse, Andy West, and the Lyndon family for their contributions to this article. And thanks to Jon Sievert for the use of his Twiggs Lyndon photos.

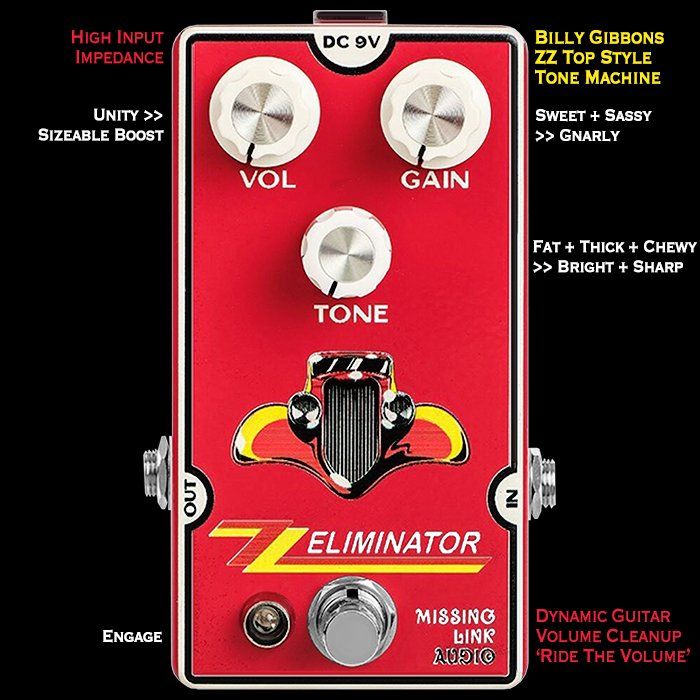

Pedals are very much like buses at times - when you get a number of certain types appearing at around the same time. We all know that pedal / circuit creation cycles can often take a year or two to develop - so it’s typically entirely serendipitous when two relatively similar pedals appear almost simultaneously - as is the case with the very recent J Rockett El Hombre, and this MLA Eliminator Overdrive.

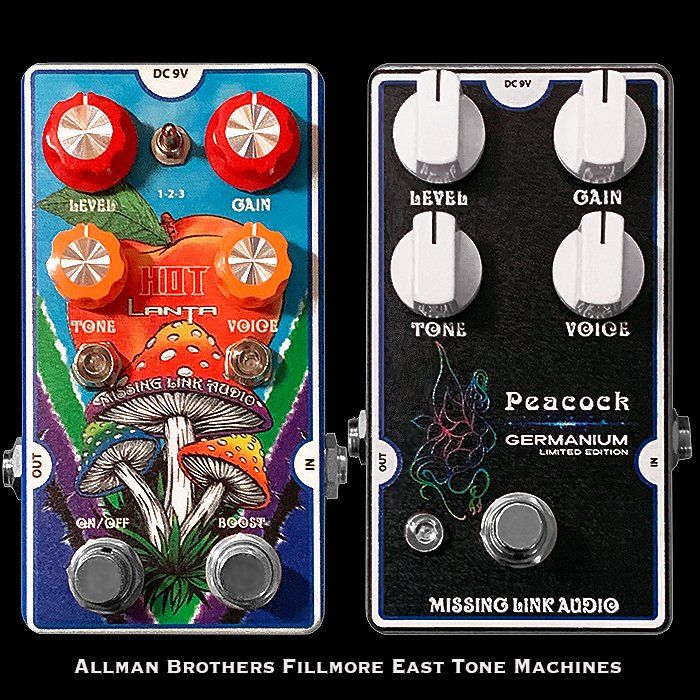

I actually ordered my Missing Link Audio Germanium Peacock well before the HotLanta was released - and that was supposed to be my first Missing Link Audio Review - while through several quirks of fate I ended up having both land simultaneously - which turns out to have been a really good thing actually!