The Fillmore Days

An Interview with award-winning filmmaker and photographer Amalie Rothschild.

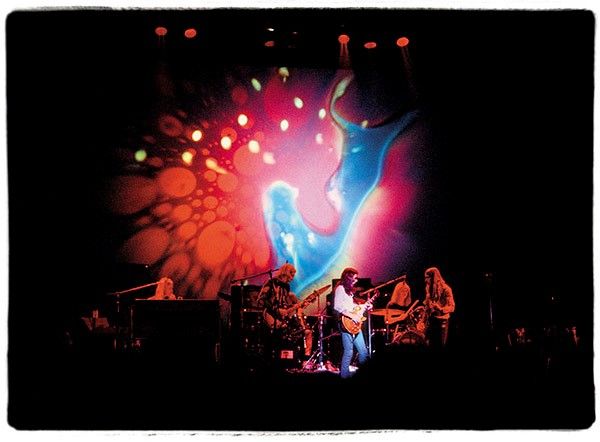

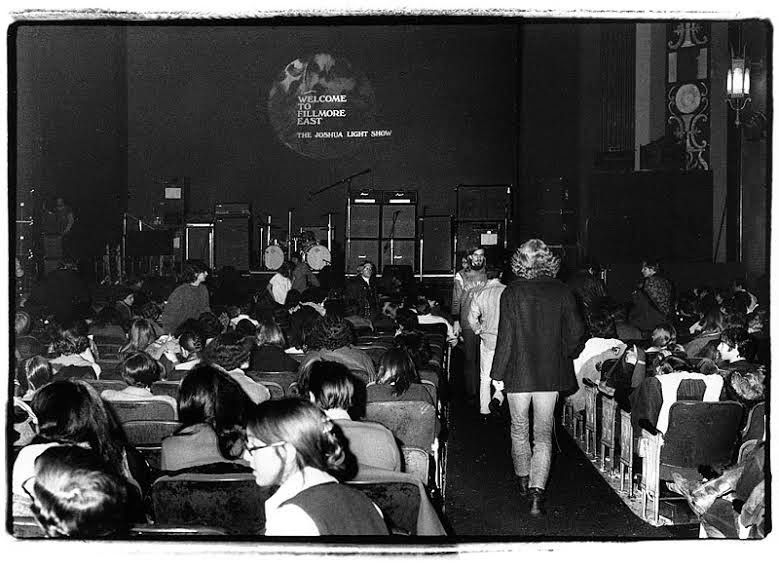

Many of her photographs feature the incredible psychedelic lightshows for which the Fillmore was renowned.

This interview was recorded in the spring of 2002 and sat on the shelf for more than 20 years before being re-discovered and transcribed to share with music fans everywhere. Amalie Rothschild is such a remarkable talent and was happy to share stories of her time at the Fillmore East. All photographs are supplied by her.

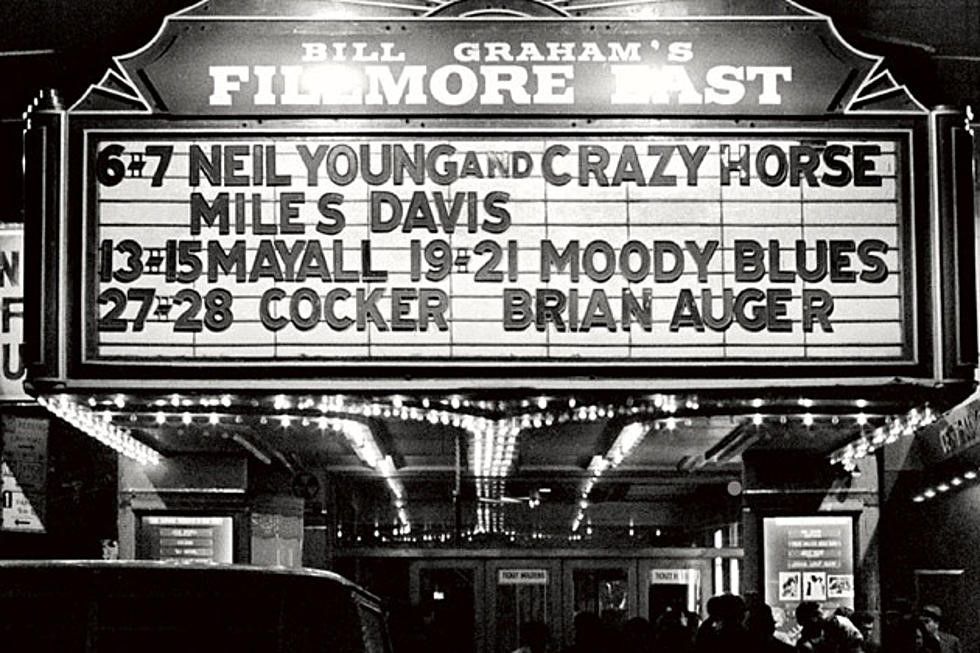

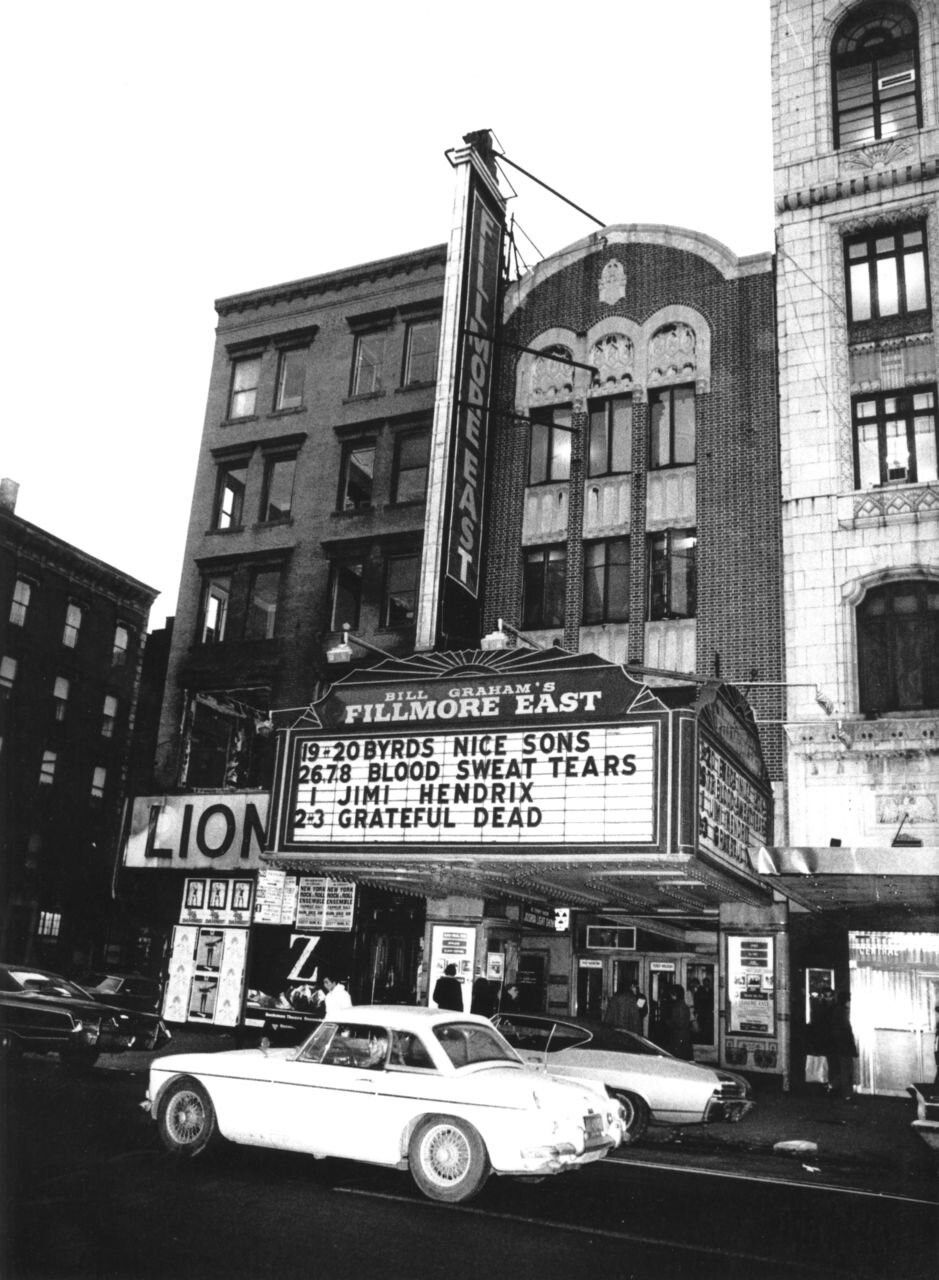

From 1968 until it closed its doors in 1971 Bill Graham’s legendary venue was her unofficial home, the place where she was witness to the Who’s premiere of Tommy, Jimi Hendrix’s New Year’s Eve concerts, John and Yoko’s unexpected encore to a Frank Zappa gig, The Grateful Dead. The Allman Brothers Band, Janis Joplin, Santana, Jefferson Airplane, Crosby Stills and Nash (and Young) and Pink Floyd amongst others. Away from the Fillmore she photographed many world-renowned artists including Bob Dylan and The Rolling Stones.

At the Fillmore East, rock music became theatre and the swirling psychedelic light shows that formed the backdrop to the musical performances defined psychedelia in visual terms. The Joshua Light Show, and later, Joe’s Lights, the pioneering light shows that deservedly received separate billing on the Fillmore East marquee, were the best in the business. As Amalie reflects, “These light shows were performances in their own right. The people behind the scenes who manipulated film, overhead and slide projectors, color organs, strobe lights and a wealth of other equipment were just as much performers as the musicians onstage.”

Interview:

Tell me about the first time you remember the Allman Brothers playing the Fillmore East.

Well, I remember the first time that they played, of course. It was fantastic. Nobody had heard of them. Nobody knew who they were. My recollection is that at any event the staff and the crew and everybody, all of us who were working there were blown away. They thought they were absolutely, you know, fantastic. And that was from the sound check in the afternoon right after they arrived.

The Allman Brothers played the Fillmore East on several occasions and recorded their biggest album there, what were those shows like and do you remember who they may have performed with?

Their first date was Friday, December 26, 1969. They were at the bottom of the bill. The second act was Appaloosa and the first act was Blood, Sweat and Tears. And they played three nights, Friday, Saturday, and Sunday. Then their next gig was in February of 1970. That was the beginning. That was with Love and the Grateful Dead.

Is it true that’s some of the Fillmore concerts would last until 6 am the next morning?

Well, it varied because there were two shows a night at eight o'clock and 11:30 p.m. And of course the best shows were at 11:30 because that's where there was, you know, you didn't have to get the audience out for the next show so they could play until six o'clock in the morning. But the six o'clock in the morning was on the very last night, the very final show. There were many other shows, mostly with the Grateful Dead when they would play until sometimes three, four in the morning, yeah. Until the bands decided that they didn't want to keep playing until late because there was no time limit. Whereas the first, the eight o'clock show, obviously that was pretty much set because they had to be finished at least at the very latest by eleven in order to get everybody out and the next audience in for the second show.

Who was your favorite during the period of the Fillmore? Did you have one?

I didn't have one favorite. I had a bunch of favorites. I mean, how can you have, I mean, it's apples and oranges. How can you pick between the Allman Brothers and the Grateful Dead and, I don't know, Laura Nyro who was one of my very, very favorites, she played there a couple of times. She was one of those marvelous singer-songwriters who did not have the fame and fortune that I felt she definitely deserved. I liked a very obscure band that never went much of anywhere called SeaTrain. You may or may not know them. They were wonderful. You might look them up. They're a bunch of albums that are still available. I loved Ray Charles. How could you not love Ray Charles? But none of the heavy metal stuff, none of the bands like Led Zeppelin. I have no photographs of Led Zeppelin. I didn't photograph the groups that I didn't like. That's the one regret I have, though, that I should have photographed them, just because I should have pictures. That would be, that's a hole in my archive. I was a purist. Of the really classic bands from that era that you would say, you know, of course, the Allman Brothers and the Grateful Dead, sort of like a tie, shall we say.

What was it like being there and being able to capture many of the moments in history of so many great artist?

First of all, you have to realize that this was the beginning of something. We were all living through it, but nobody knew this was the beginning of something with the kind of advantage of hindsight that one has 20 or 30 years later. But we all sensed that something fabulous was happening. I think Bill Graham knew it was developing into something big but, But I don't think anybody had any idea how it was going to develop initially, commercially. And it was an age, it literally was an age of innocence. And there were no real rules. So there was no such thing as a rock photographer. There were photographers like me who started taking pictures of the musicians. And I know that I felt something extraordinary was happening because I started documenting it without any clear purpose or understanding of why I was drawn to do that. I just was. And because I was there and there were no holds barred of any kind, nobody controlled anything. It was just a chaotic, marvelous place to be with wonderful things happening. Nobody said anything. And I could take any pictures I wanted at any place at any time. And I was paying for it. I bought the film. I processed the film. It was mine. And some of them were used in the programs later on. And some of my pictures were on the walls in the offices. But there was never, nobody had any sense of ownership. There was no sense that I couldn't do this and that anybody else wanted them.

Were the bands that played the Fillmore East always good?

Obviously, there were good bands, fabulous bands, mediocre bands, and a few real clinkers. I think the Consensus was the very worst band that ever played there that was nobody understood how they even got booked was a band called, Sir Lord Baltimore. And the story of how they did get booked is in, I think, the Bill Graham bio. I mean, it was one of those deals where the management agency foisted them on the bill in exchange for being reasonable about the booking of somebody else they represented. You know, it was a new band. They wanted to get them, package deals. Still the same way today. Vanilla Fudge was another band we couldn’t stand.

How loud could the bands get?

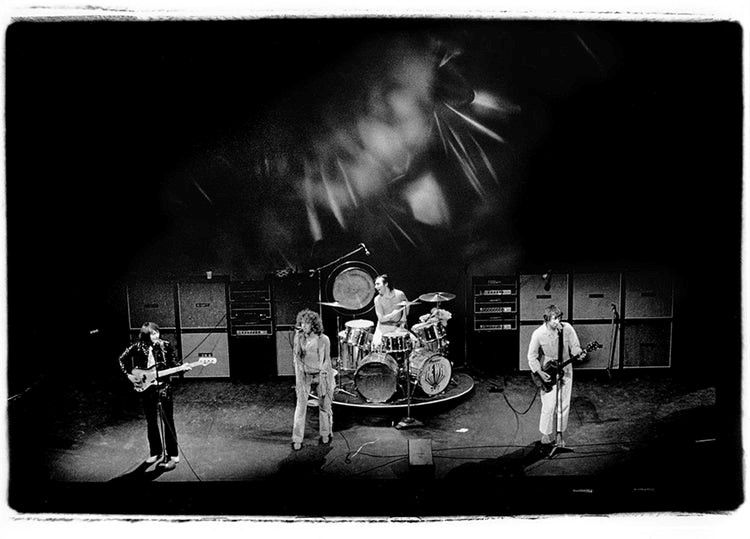

I had troubles with Mountain at the time because they were so loud it hurt. The Allman Brothers and the Dead you could listen to, they weren't so loud. And it's important for what I'm doing, both what I've done in my book and what I hope to do with the feature film that I'm starting to make based on my book, which is that all of the real technological innovations for the presentation of rock music were invented at the Fillmore East. It was a marvelous environment because it was a real theater with a stage and a proscenium arch. The audience were in reserved seats unlike the chaotic ballroom scene on the West Coast and Bill Graham absolutely believed in giving the public their money's worth, which meant a professional show.

How advanced was the Fillmore for a music venue of that day?

In a theater, you've got certain obligations there. You have to have superb sounds. And this, the Fillmore East really perfected what it's really noted for, and this is where John Chester comes in with Lyon Hart. And they developed and built a superb in-house sound system with a multi-channel mixing board with sliders. This was at the dawn of this technology. And Bill Graham understood the importance of this and actually put up the money for his technical staff to build this stuff in-house, install it, and do it. And I have all the photographs of all of this, of the construction of the sound system and all the pieces and all the stuff. And the Fillmore East was the only venue in the entire country where the Grateful Dead used the house sound system and not their own. And that sound system was so good that it didn't, the idea was not to kill people's eardrums, but to give them a fabulous musical experience. They had originally, I think the original mixing board was eight and then they expanded it to 12 channels, which at the time was, you know, that was a lot.

What did it take to operate the Joshua Light show & Joe’s Lights?

What was fabulous about the Fillmore East and what my involvement really entailed was the technical environment. It wasn't just rock and roll. It was a real working creative theatrical environment where there were top notch technicians and creative technical type people innovating in the presentation of the music. So I mean the light show has never been surpassed in its quality and none of the computer-generated stuff that you see today even comes close even though some of it is superb. This was even better. And it was a group of the Joshua Light Show and Joe's Lights. It was a group of six

visual artists who improvised visual music as a backdrop and it wasn't just backdrop, it was in symbiosis with the bands out front. And they actually worked harder than the musicians did because for the most part they played three sets every show whereas the musicians only played one set a show. They didn't play every single show. There were some groups that didn't want a light show. But for the most part they accompanied almost everything. They were paid weekly by Bill Graham.

How innovative was Bill Graham and his staff?

The Fillmore East was a working theater. There were at least four shows every weekend, two on Friday and two on Saturday. So there was a resident house staff that was working there perfecting the systems. I mean, people had a job and there was a consistency. And every week there was one great group after the other. You take a look at the marquees and it just blows your mind. And no, we didn't, none of us knew at the time what, you know, how significant this was going to be in the future, but everybody had a visceral gut sense that this was good music and this was great stuff. And it was a heady, heady, exciting, invigorating place to be because not only were you getting off on all this music, but there was the incentive to make it better. In that sense, Graham was an enlightened manager because in the long run it really did matter to him to give the public a good show. So even if he had made all of his money, if his technical people came to him and suggested that they could do this and do that to make the show better, you know, build a better sound system, do a special production for a given group because blah, blah, blah, and I'll get into that in a second.

If his technical staff made a good case for him, he respected them and he would pony up with the dollars to let them do it. And that is a way of getting the best out of people and having people who care about what they're doing and are having fun while they're doing it too. And I mean the best example of that, which there's a whole section about it in my book if you haven't read that, was when the Who Did Tommy. And that had been sold out long in advance and I actually was the ringleader in pulling this together because I said to the tech staff, the guys, I mean my buddies, Chester Langhart, Bob Goddard and Bob C. and Joshua of the Light Show naturally because that's where it all began, was that here they're going to, the Who are going to perform Tommy for six nights in a row and we can't just have the Light Show just do their, it can't just be a normal concert. This is something special. We've got a libretto. It's an opera. We should do a special production. We've got stuff that we can do. And I convinced the guys that that was, you know, that it wasn't hard to convince them.

So they then pulled it together, made a proposal and they went to Bill Graham and the shows had been sold out for months and he put up a $5,000 budget for Tommy. And we built the new 40-foot-wide arc Light Show screen. They got some improvements to the sound system. I got a $500 budget to make special film effects for the Light Show and the Light Show got additional money that we made flying mats and for them to develop additional software in order to create a visual, you know, accompaniment to Tommy that could be repeated night after night. It all connected. There was something there that you could do to make it a real production and we did.

There was no in-house taping or anything at the Fillmore East. But the groups, I mean lots of the groups loved the light show. They sometimes, you know, have their backs to the audience watching what was going on the screen behind them. And as I said, there were a few groups who felt upstaged by the light show and didn't want a light show like Crosby, Stills and Nash. They were very vehement about that. They wanted just a black backdrop and they had a Persian carpet out on the stage and sat on stools and so forth. Joni Mitchell didn't have a light show. I mean there were others. Laura Nyro didn't have a light show. Some of the very intimate, you know, women singer-songwriters where you had a very romantic, intimate kind of a concert setting didn't have a light show where it would have been overpowering and, in some cases, inappropriate.

In Conclusion:

Amalie Rothschild was a very generous person and spent considerable time sharing stories with me on the day of the interview in 2002. Her work can be found on display at www.amalierrothschild.com.