The Sound of the Fillmore East

How Live Sound Bled into the Records We Know

Why is At Fillmore East Still Stuck in Our Minds?

Studio albums of the 1960s and ’70s were exercises in control. Bands tracked in isolation, producers overdubbed takes, engineers sculpted final mixes into something clean and permanent. Yet decades later, it’s not only those polished records that live on. It’s the live albums — above all At Fillmore East — that still feel electric, urgent, unforgettable.

The mystery is why. Was it only the bands, or did Fillmore’s own house sound — Bill Hanley’s horns, woofers, and racks of McIntosh amplification — leave its fingerprint on the recordings?

Hanley Sound: Building the Foundation

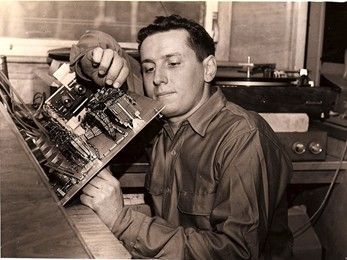

Bill Hanley began in Medford, Massachusetts, in the late 1950s, rigging makeshift systems for rallies, dances, and folk clubs. His philosophy was simple: music should be heard clearly and without distortion. Standard PA systems of the day were meant for speeches, not art. Hanley wanted fidelity.

He experimented constantly. Altec “Voice of the Theatre” loudspeaker cabinets were stacked higher and tuned harder than their manufacturers ever imagined. Mixing was moved offstage into the audience — so the engineer heard what the crowd heard. He believed in power, but also in clarity.

As Hanley once put it: “What’s important in a sound reinforcement console is speed. Get everything into the audio engineer’s field of vision. You’ve got to be able to touch and feel everything.” (Hanley, RE/P Interview, 1986).

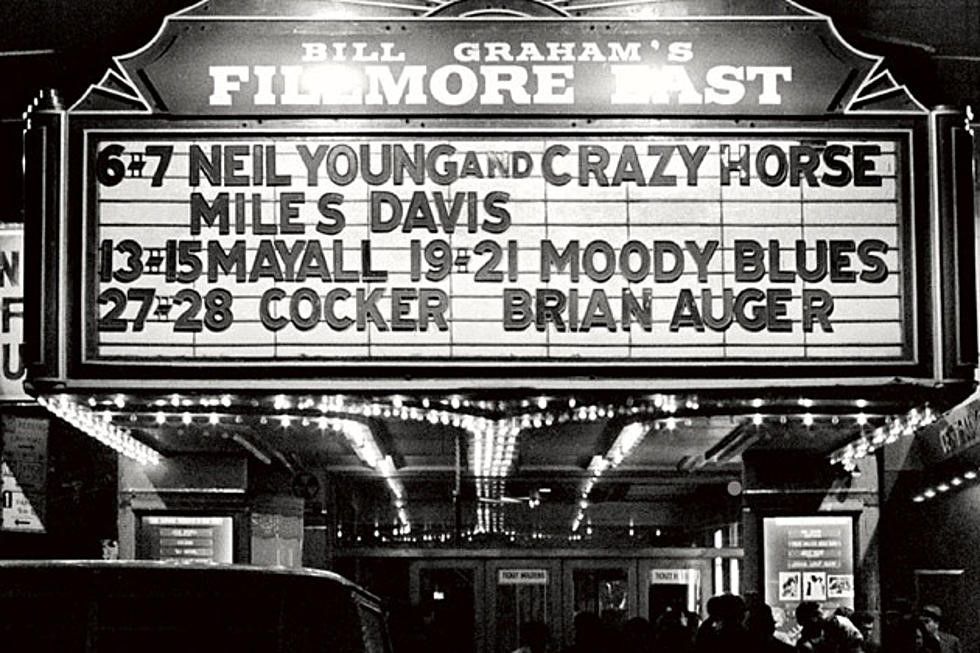

By the mid-1960s, Hanley Sound was running systems for Newport, Boston clubs, and New York promoters. When Bill Graham sought a reliable sound partner for his new East Village rock palace in 1968, he called Hanley.

Woodstock: The Trial by Fire

One year later, Hanley faced the biggest challenge of his career: Woodstock. Half a million people, an open field, storms and chaos. No system had ever been asked to do this before.

Hanley built towers of Altec multicellular horns powered by racks of McIntosh amplifiers. Signal snakes hundreds of feet long carried feeds to a front-of-house tower in the audience — a radical idea at the time.

“We had done a lot of tests and had a lot of failures with JBLs on the high frequencies,” Hanley recalled. “We got into the Altec 290 compression drivers because they would stay together longer.” (RE/P Interview, 1986).

Against all odds, the system held. As Hanley later said: “The only things that didn’t fail were the sound system, the water supply, and the stage security.”

Woodstock proved that live sound could scale to unimaginable sizes — and that Hanley’s methods worked.

The Fillmore East: A Theater Becomes an Instrument

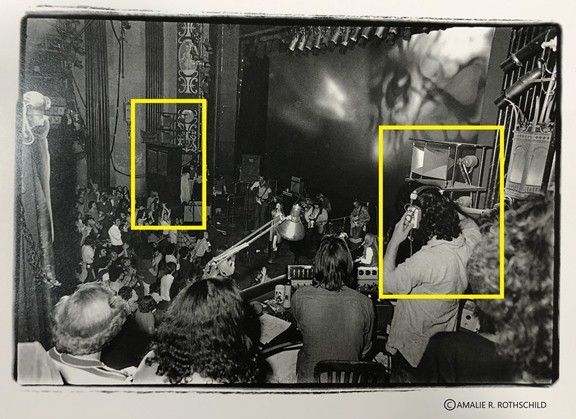

Back in New York, Graham’s Fillmore East was something different. Built in the mid-1920s as the Commodore Theatre, the building seated about 2,600. Its long, narrow auditorium and wraparound balconies weren’t designed for rock bands — but Hanley turned those quirks into strengths. It is reported that he decided on a 35000-watt 26 speaker system design.

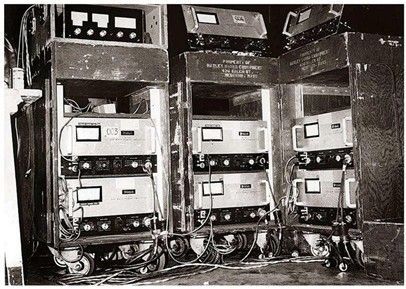

John Kane’s biography of Hanley notes: “Hanley Sound supplied the house sound systems for both the Fillmore East and West, using primarily horn-based designs powered by McIntosh amplification.” (The Last Seat in the House, 2019).

Amalie Rothschild, house photographer, remembered: “The Fillmore East really perfected what it’s really noted for … they developed and built a superb in-house sound system … the Grateful Dead used the house sound system and not their own.”

The Fillmore wasn’t just a venue. With its plaster ceilings, balconies, and Hanley’s carefully tuned horns, it became an instrument in itself.

The Albums That Carried the Room

From those walls came some of the greatest live albums in rock:

- The Allman Brothers Band: At Fillmore East (1971)

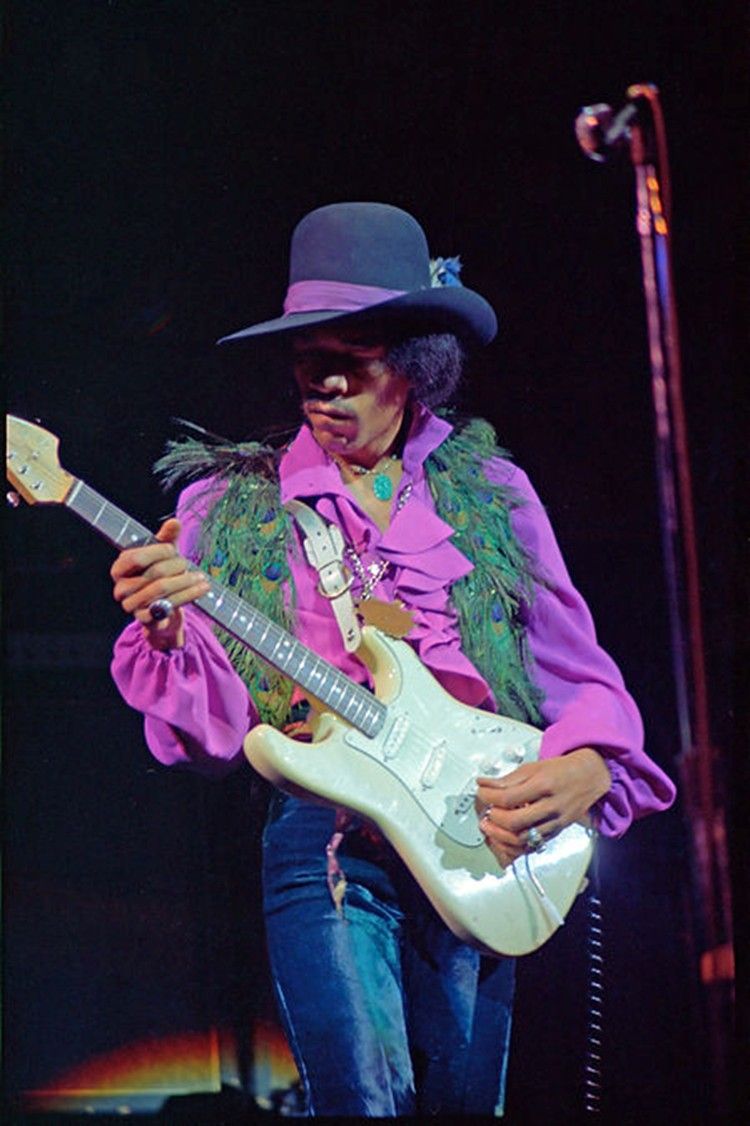

- Jimi Hendrix: Band of Gypsys (1970)

- Grateful Dead: Live/Dead material (1969–71)

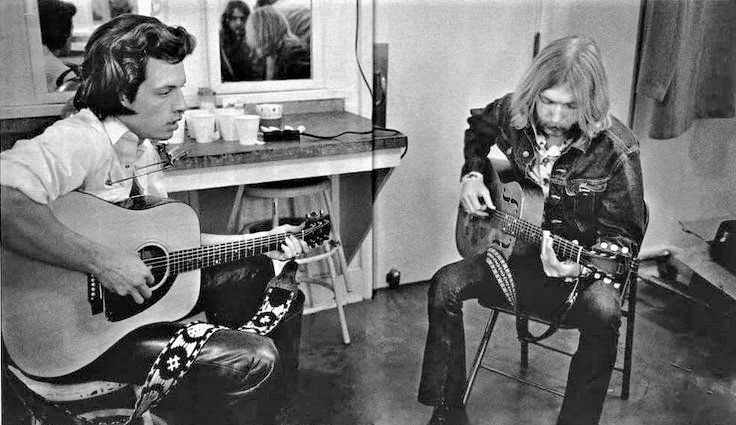

These records feel different because they are different. Producer Tom Dowd, working with engineer Aaron Baron, didn’t only capture dry mic feeds. As Baron noted, “On the album you can hear the room mix being faded into the dry mix at the beginning of some of the tracks.”

That room mix included Hanley’s Altec horns and McIntosh power amps bleeding into the microphones, embedding the Fillmore’s character into tape.

The Horns on Record

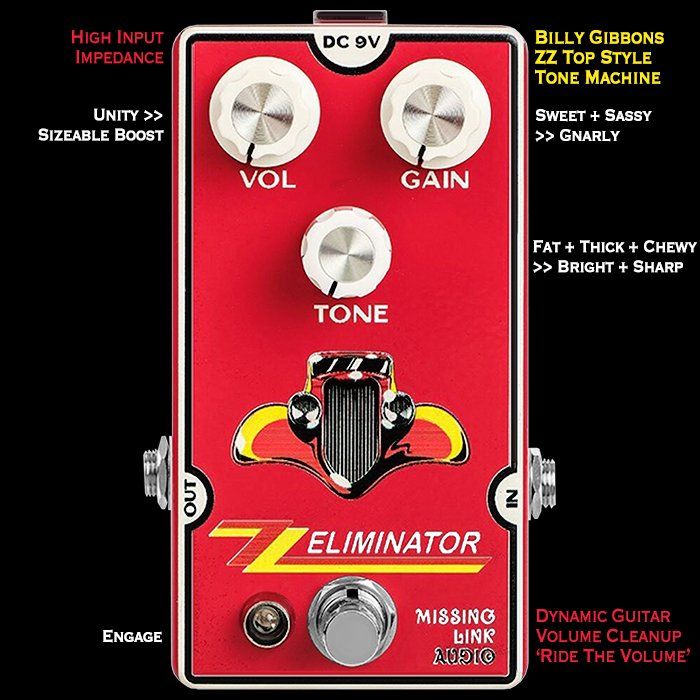

The Fillmore East system revolved around Altec 288 large-format compression drivers on sectoral horns for mids and highs, Altec 515 woofers for low frequencies, and McIntosh amplifiers for reliable power.

Hanley explained why stacking was critical: “Speakers had to be stacked high, because such stacking compresses the sound into the audience area.” (The Last Seat in the House, 2019). In modern terms, his vertical arrays provided directional control, putting the sound where the people were and minimizing spill.

That precision is why, listening to Statesboro Blues, Duane Allman’s slide doesn’t just sound like a guitar amp mic’d onstage. It sounds enormous, almost like it’s being projected through the horns themselves. The PA became part of the instrument chain.

The Room as Its Own

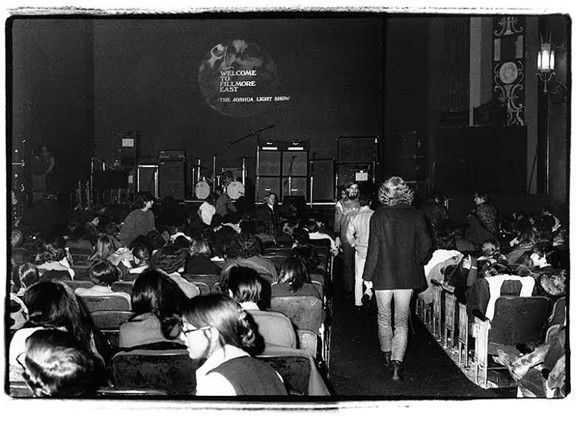

Walk into the Fillmore East on a concert night, and you’d have felt it. Two balconies curving around the stage, ornate plaster ceilings glowing with Joshua White’s liquid light shows, 2,600 people packed shoulder to shoulder.

“These light shows were performances in their own right … the people behind the scenes … were just as much performers as the musicians onstage,” Amalie Rothschild recalled.

And then the sound hit. Dickey Betts later said the air at the Fillmore was “alive and magical.” That wasn’t just metaphor. The Altec horns, McIntosh clarity, and reflective architecture created a feedback loop between band, room, and audience.

Producer Tom Dowd’s tapes captured it. Listen closely, and you can hear the room itself rising into the mix. The Fillmore wasn’t just hosting the music — it was playing along.

The Great Tone Chase Is On

Decades later, guitarists are still chasing the tones that came out of the Fillmore East. Duane’s slide, Dickey’s lyrical runs, Jerry Garcia’s crystalline leads — all became benchmarks. Players swap pickups, hunt vintage Marshalls, and argue over Tom Dowd’s fader moves.

But how much of that tone was the player? How much was Dowd? And how much was the Fillmore’s horns and plaster walls, bleeding into microphones?

Tone lives in fingers and wood and circuits, yes. But those records remind us it also lives in air — in the rare alignment of player, producer, sound system, and room.

Why There Have Been No More Recordings Like It Since

If albums like At Fillmore East feel singular, it’s because they were. The bands were at their peak, Tom Dowd was at the board, and Bill Hanley’s horns were tuned to a 1920s theater that just happened to love rock and roll.

After 1971, rock moved to arenas and stadiums. PA systems evolved to be neutral, designed for coverage, not character. Rooms grew too large for intimacy. Sound reinforcement became invisible — a virtue for consistency, but a loss for magic.

There has never been another Fillmore East, with Hanley’s system and Dowd’s faders capturing the room itself. That is why, half a century later, those recordings don’t just sound alive. They are alive.